Human Vs. Civilisation

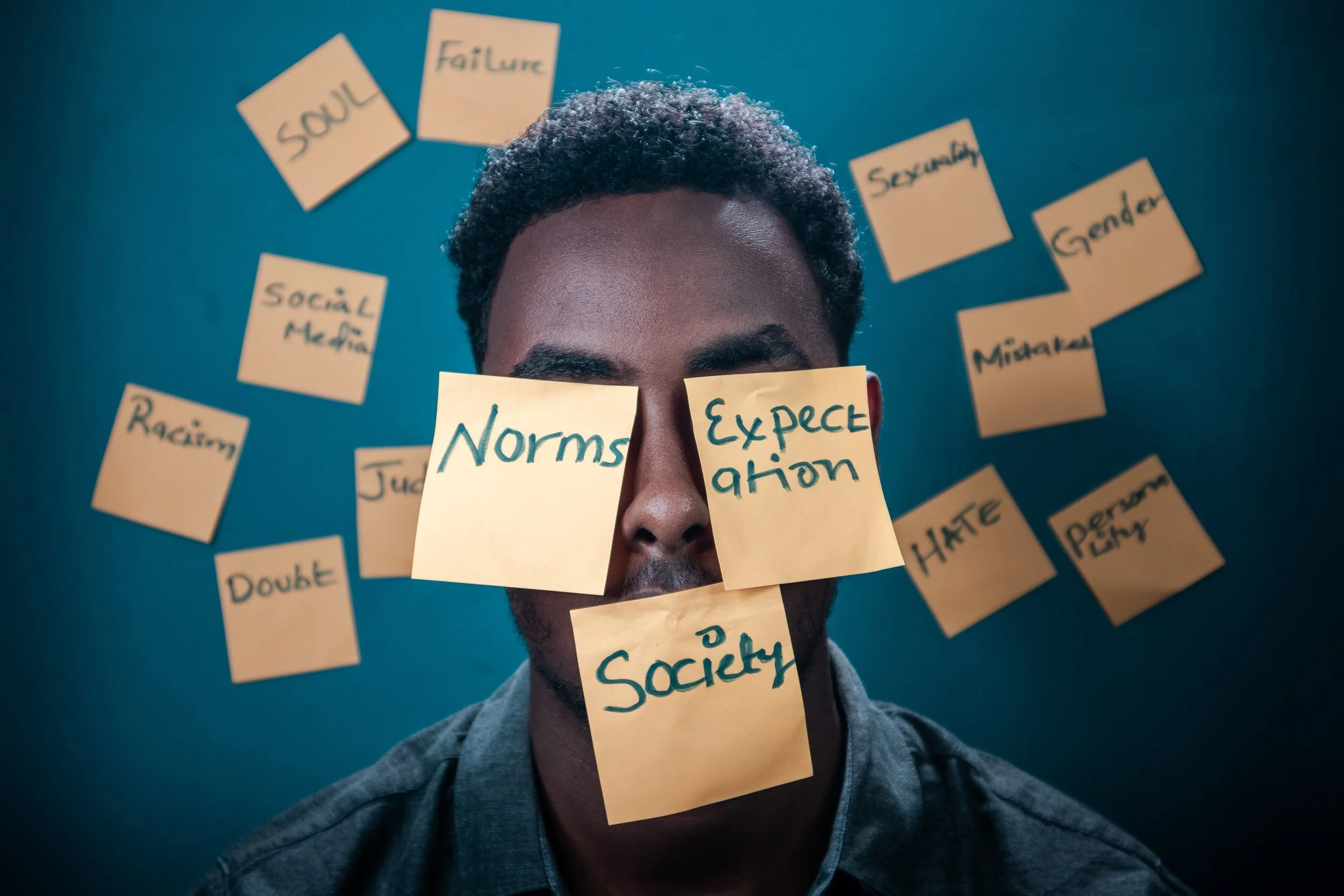

The more I learn, the higher my conviction is that as humans, our greatest struggle arises from context. Context… our physical, social, spiritual and cultural surrounds and influences. From our very beginning we are at the mercy of our environment. How others relate to us, the stories about our world, our history and our future we are exposed to, our safety or lack thereof, and the ubiquitous intensity of media and advertising messaging. Steeped in these specific narratives, we develop with such context as our compass. It becomes our point of reference for determining our acceptability, worth, definition of success, behavioural repertoire, and ultimately, our wellbeing.

The way in which civilisation has violently disconnected human existence from our prehistoric lifestyle, seems to me to be central to understanding the level of suffering in our world.

My recent reflection has motivated me to write a series of blogs that unpack this idea.. to frame contemporary human difficulties through this lens. I will write my reflections to make sense of the presence of suffering within anxiety, parenting, relationships, loneliness, ageing, addiction and adolescence from this perspective.

Of course this is not an original idea, and there exists a multitude of theories that posit the same argument. Notably, functional contextualism serves as the basis for the therapeutic approach of Acceptance and Commitment Theory. It is no surprise that this approach forms the basis of my own therapeutic work with clients.

I leave you with a question to consider that may prompt your own reflections. An invitation to reflect upon the role of context within your own life. Permission to reconsider any self-blame when stuck in the pain of loneliness, stress, poor body image, a negative relationship with food or weight, or the pervasive angst of feeling ‘not good enough’.

Anthropological research has consistently converged upon the idea that individuals within a hunter-gatherer society worked an average of 3 hours per day. Just imagine how your mood, energy, health leisure, general wellbeing and relationships may be different if your work day was finished in three hours. This extends further when the type of work is considered, as generally work comprised the kind of activities that form many people’s leisure pursuits today (fishing, hunting etc.), and was always undertaken in the context of social connection. Sounds nice, right?

Self Care

When was the last time you engaged in self-care?

Self-care is when we engage in an activity that promotes our own wellbeing. This might be promoting our mental health, physical health or spirituality.

For many people, we may go a long time having not engaged in self-care. This may be due to an overwhelming schedule or other priorities seeming more pressing. We may also take a week off a self-care activity due to a deadline, only to realise that its now been months that we have not engaged in self care.

When we neglect self-care, we might begin to notice an increase in experiences such as irritability, anxiety, anger, sadness, intolerance, rumination, guilt, emptiness, lack of motivation and feeling burnt out.

There are things that we can do in the face of these experiences in order to promote our physical, mental and spiritual well-being.

Self-care includes activities where afterwards we find ourselves feeling that little bit more relaxed, present, content or even joyful. This might include:

Listening to music

Being in nature

Exercise

Reading a book

Cooking/eating a balanced meal

Mindfulness activities

Writing in a journal

Having a tea

Playing with pets

Cleaning up a space

Taking a walk

Deep breathing

Spiritual activities

As a way to help maintain our engagement in self-care activities to maintain our wellbeing, it can be helpful to find a way to incorporate them into the daily routine. This may look like a block of time each day assigned to self-care or it may look like self-care scattered throughout the day such as taking 5 minutes between meetings to do some deep breathing and play some relaxing music. For the busy schedule, activities such as eating meals which might ordinarily be spent doing work or scrolling through the phone can become self care by eating the meal mindfully.

With the implementation of self-care into the daily schedule we often begin to find we have that little bit more tolerance to handle challenges of the day as they arise & find ourselves feeling more peaceful. We may feel more connected and content in our mental, physical and spiritual wellbeing. How might you be able to incorporate self-care into your daily routine?

5 ‘one off’ things you may want to try this Christmas season to assist your mental health

Before I start, the allure of a ‘quick fix’ is so tempting in regards to our mental health – we’re often looking for something fast and easy to alleviate unwanted symptoms. In my experience, however, these are unfortunately rare in regards to mental health treatment. Mental ill health is often caused by long-standing patterns (such as internalising negative thinking styles, or repeated avoidance behaviours, or ongoing chronic stress) or other factors (such as genetics and physical health) which aren’t able to be reversed or changed immediately.

Having said that, here are some things that I often recommend clients try out at least once during their treatment journey in order to see what they notice as that change is made. You might want to trial one, or all five, over the festive season.

Eliminate caffeine

Australians love our coffee and caffeine is great for many things, including waking us up on a Monday morning or being the perfect drink to accompany a brunch. However, caffeine can inadvertently have negative effects at times on our sleep and our anxiety. Regardless of how much or how frequently my clients drink coffee, I often recommend they try and reduce or eliminate caffeine (including energy drinks, teas, colas, etc) for a period. Perhaps as short as one day or maybe as long as 1-3 weeks. This can give us a chance to see if the caffeine is impacting (or not!) how restful and regular our sleep is, or how prominent our physiological and cognitive symptoms of anxiety might be. You may want to embrace decaf, herbal teas, or other caffeine free soft drinks.

2. Eliminate alcohol

Similar to above! Many Australians drink alcohol, even just socially (however evidence does suggest our rates of drinking are declining…), and alcohol in moderation is perfectly fine as a lifestyle choice. However, alcohol can possibly also play a role in our sleep quality, and anxiety and depression symptoms. Again, perhaps try reducing or eliminating alcohol, to see what impact is has. Many clients report finding alcohol (even in small amounts) can sneakily but significantly cause less restful sleep, more anxiety (or ‘hangxiety’ – hangover anxiety!) symptoms, or exacerbate their depression. Thankfully, the range of alcohol free drinks has expanded significantly in recent times, making reducing or eliminating alcohol even easier.

3. Do something playful

The older we get, the farther away (literally and metaphorically) we get from our childhood. Gaining independence and autonomy as an adult can be very liberating, but adulthood can also come with increased responsibility (with work, finances, family, caring responsibilities, etc). Often in the midst of responsibility we lose touch with our playful selves; our spontaneity, our creativeness, our silliness. Sometimes I suggest clients try and reconnect with this side of themselves – maybe next time you walk past a playground try and swing on the swing or go down the slippery dip. Maybe you want to dance to a favourite song, by yourself or with someone you care about. Maybe you want to try write a poem, or compose a tune, or get out some paints or crayons, without caring how ‘good’ the outcome may be.

4. Spend some time alone

Note, this won’t apply to everyone - many people struggle with loneliness and isolation and wish they could spend less time alone! However, I’ve seen many clients who, for one reason or another, very rarely spend time alone and often fear it. Whilst humans are social creatures and human connection is incredibly healing and important, there can be many benefits of solo time. I often suggest clients try and set aside a time to be alone, whether it’s 15 minutes without their phone sitting outside, 1 hour for a solo walk, a dinner or meal by yourself, or even a solo holiday! Often it’s not until we are by ourselves that we are able to truly connect with ourselves, let certain thoughts and feelings come to the ‘surface’, and learn other regulation skills. Being more comfortable with being alone can also have the added benefit of enriching our relationships because we are able to more freely ‘choose’ to be with someone, rather than because of a fear of being alone.

5. Plan a break or holiday even when you don’t ‘need’ it

I work with many people who feel like it would be a ‘waste’ to take a holiday if they don’t really need it. However, prevention is always better than cure! Taking a break even when you don’t feel like you 100% have to can be an excellent way to prevent burnout. Even if it’s just taking one day off for an extra long-weekend, there can be many surprisingly nice things about taking a break or holiday before you feel like it’s necessary. It can be nice to have a ‘staycation’ which involves no travel, no airports, no driving, no packing and unpacking, no plans. Or a midweek day off where you can do nothing, or catch up on life-admin, or explore your own city, or see a friend with a different schedule. When we only take holidays when we need it, we often need more time to ‘unwind’ before we can actually enjoy the time off. We arrive at our breaks exhausted and stressed, sometimes collapsing rather than enjoying the time off. Before the end of the year, you may want to look forward into next year and plan when you may want to take a quick break :)

5 Simple Cornerstones of Mental Wellbeing

Depression and anxiety are very common psychological disorders that are characterised by high levels of distress and negative impacts on functioning in daily life. However, even when these symptoms are not at a clinical level, the impacts on an individual can still significantly affect their quality of daily life. It is very important for everyone to prioritise and support their mental health, both preventatively and to improve difficulties.

Reading a research paper from psychologists at Macquarie University recently, I was reminded of the importance of the small daily things that we do, that contribute so much to improving and maintaining our mental health.

Two studies examined which activities and behaviours (out of 500) were used regularly by people, and were effective in supporting their mental health, as reflected in clinical measures of anxiety and depression. 3000 people were involved in each study. The studies identified five domains of daily behaviours or actions that were consistently associated with better psychological health.

In order of importance, the 5 key areas identified were:

1. Meaningful activity: Do things that are in line with your values. Pursue things that you are passionate about - that are fulfilling, satisfying, or enjoyable.

2. Healthy thinking: Treat yourself with compassion and respect, accepting that you are not perfect and that things do not always go according to plan; do not be ‘pushed around’ by unhelpful or unrealistic thoughts.

3. Having goals and making plans: Set realistic and achievable (SMART) goals, and take action to achieve them; make plans and act on them.

4. Healthy routines: Keep (largely) to a daily routine, with regular bed and waking times, regular healthy meals, and regular exercise patterns.

5. Social connections: Spend meaningful time with others; seek out positive people; connect with others regularly (in person, on the phone, or online) and chat about what’s happening in your daily life.

While these factors may seem obvious when they are listed like this, it is easy to lose sight of them in the whirlwind of life’s demands, or when we are struggling.

We are generally aware that our mental health is strongly connected to the little things that we do on a daily level, such as spending time with friends, going for a walk, or doing a meaningful activity. However, it is also important to be aware that when we are feeling distressed or overwhelmed, these supportive behaviours are often lost from focus or abandoned. In addition, when we let these behaviours slip, we are more vulnerable to feeling anxious and/or depressed. This sets up a downward spiral of distress and reductions in supportive behaviours.

Having the skills to implement and maintain the key supportive behaviours for good mental health, and the awareness to prioritise them, are central to psychological wellbeing. This is why learning skills and strategies that align with these key domains are often part of psychological treatments.

While the very simplicity and value of the simple daily things we can do for our mental health makes them reassuring and achievable, it is also makes it easy to underestimate their importance and let them slip from our focus. What daily behaviours could you choose to start, build or re-establish in your life? How might you keep these in focus?

Reference

Titov N, Dear BF, Bisby MA, Nielssen O, Staples LG, Kayrouz R, Cross S, Karin E

Measures of Daily Activities Associated With Mental Health (Things You Do Questionnaire): Development of a Preliminary Psychometric Study and Replication Study, JMIR Form Res 2022;6(7):e38837

doi: 10.2196/38837

Defusion from Thoughts

Do you ever find yourself having an emotional reaction to a thought you have had? Perhaps you felt anxious, angry, worried or sad. That thought might then lead to a stream of other thoughts that seem to fuel that fire of emotion which we may call a negative thought spiral.

One strategy that can be helpful when we are finding ourselves wrapped up in our thoughts is called defusion. Through this strategy you may find that your emotional reaction in response to your thought is different. Here’s how to do it. Say to yourself out loud or in your head a thought that distresses you and then rate your level of distress out of 10 (10 being the most distressed). Then add “I’m thinking…” ahead of the original thought and rate your level of distress out of 10. See if it has changed at all. Lastly, add “I noticed that I am thinking…” ahead of the original thought. Did it change again?

This strategy can be helpful for creating some space between ourselves and our thoughts. This space may provide some relief from the emotional intensity of the thought which may consequently put us in a better position to consciously choose our next action.

2 Quick Questions for Thought Challenging

As most psychologists will tell you, the way we think and the way we speak to ourselves has a huge impact on the way we feel and act.

According to CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy), an important part of mental wellness is, firstly, being aware of our thinking and the power it can have over us, and secondly, being able to challenge thoughts that are creating distressing feelings or unwanted behaviours.

Thought challenging can take many forms, but here are two quick questions I often get clients to ask themselves when they notice themselves getting stuck in something.

(Of course, these questions can only be asked once you’ve tuned into your self-talk and identified a few specific thoughts that are possibly contributing to your current headspace).

Is this thought true? (Or, how true is this thought?)

The old adage is “thoughts aren’t facts”. Our brains aren’t objective computers which produce factual output – they are just a ‘good enough’ organ, highly impacted by our sensory systems, our memory, our upbringings and worldviews. Just because you are having a thought, does not necessarily make that thought true. Sometimes we miss or discount aspects of a situation because we don’t notice it or we undervalue it.

You may need to ask yourself ‘how true is that?’. What is the evidence for this thought? What is the evidence against it? What am I basing this thought on? Have I missed some evidence to the contrary? Am I magnifying one particular interaction or comment and generalising?

For example, a common thought for people with social anxiety is “I will be awkward”. Asking yourself ‘is this thought true?’ may involve trying to be more specific about what you mean when you think ‘awkward’, and then finding concrete examples of when that has been true before (e.g ‘I went in for a handshake instead of hug today’ or ‘I left a long pause in-between statements at the job interview last month’) but also looking for concrete examples of when it has not been true (e.g. ‘A friend laughed at my joke yesterday’ or ‘I got invited to a social gathering last week’).

Is this thought helpful? (Or, how helpful is this thought?)

Consider what the consequences are (positive or negative) when thinking like this. Does this thought lead me towards my values or away from them? Does this thought lead me to helpful and effective problem solving or am I getting stuck? What behaviours do I engage in when I think like this? What feelings and emotions come from this thought?

Using the answers to these questions, we can understand whether or not a thought is helpful. Often, thoughts that are less true are less helpful. Sometimes, however, a thought may be ‘true’ or have strong elements of true, but it’s still very unhelpful.

For example, using the socially anxious thought “I will be awkward”. Perhaps I recognise that I do have awkward tendencies! (Doesn’t everyone?!). However, I may also recognise that getting fixated on the thought “I will be awkward” takes me away from my values (e.g. I avoid parties, or over-prepare for social interactions, and I pay close attention to how much my hands shake). Getting stuck on the thought “I will be awkward” may also make my ‘awkwardness’ worse, perhaps I avoid eye contact as a safety behaviour, or I drink excessively to manage my anxiety but end up saying things I regret later. In this instance, the possible truthfulness of the thought may be less important than the unhelpfulness of the thought in directing my behaviour.

Now what?

After examining our thinking, it may be helpful to try and create a new balanced thought, taking into account how true and how helpful it is. Instead of “I will be awkward”, perhaps we might think:

- I may be awkward, and I still want to go to the party

- I’m never as awkward as I think I’m going to be

- Everyone gets awkward sometime

- I may or may not get awkward, I’ll have to see how the event goes

Calm Body, Calm Mind - The power of 'grounding'

While we generally consider the experience of emotions to be primarily in our minds, in reality emotions are equally experienced and expressed in our bodies. Many fundamental emotions are deeply connected to the fight/flight/freeze response, which occurs subconsciously in the more primitive and survival-oriented parts of our brain.

Consider how intense emotional experiences such as anxiety, fear, anger, panic attacks or flashbacks make you feel in your body. Many people experience feeling shaky, jittery, or queasy, while others feel detached, absent or ‘in freeze mode’. As stress hormones are released, our breathing and heart rate increase, and our muscles tense, while at the same time our digestive and immune systems and ‘thinking brain’ (prefrontal cortex) are muted. This is our sympathetic system response to perceived danger.

Importantly, the fight/flight/freeze response is not under our conscious control. We cannot just direct our body to relax and calm down. Luckily, our bodies do have complementary system (the parasympathetic response) that helps us to calm ourselves and return our system to a more balanced state. This relaxation response is also known as ‘rest and digest’, as it slows our breathing and heart rate, releases muscle tension, and helps you calm down, rest, and digest.

As noted earlier, we can’t effectively think our way to calm once our survival-oriented fight/flight/freeze response has been activated. Instead, it is generally more effective to use physical body-based skills to engage the relaxation response.

There are a number of body-based, or physical, skills that can be used to engage and strengthen our body’s calming parasympathetic system response, so as to return our nervous system to a more balanced (emotional) state. These include deep/calm breathing, progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) and grounding techniques. Grounding activities are one of the best ways to calm your body and anxious or overwhelmed mind (including if you are in ‘freeze mode’).

So, what is grounding, and how does it work?

Remember that our fight/flight/freeze is activated in response to perceived danger, even if you are actually safe. Anxiety, trauma responses and other overwhelming emotional experiences are often associated with frightening memories of the past or anxious worries about the future, in which case you are perceiving danger, but are actually safe.

Grounding activities connect you to your present moment experience, increase your awareness of your body and physical experience, and allow you to realise you are safe in the present moment. We use breathing and our five senses (sight, touch, hearing, taste and smell) to anchor us to our bodies and our surroundings, and regain control of our experience. By activating our calming system, we gain the capacity to constructively make sense of our memories and thoughts, and move past or resolve them. So this is a really effective way to start processing intense emotions and treating anxiety and trauma. Learning how to calm your body is an important skill to learn before engaging in more cognitive or thought-oriented processes.

Some simple grounding exercises to try

Calm breathing

When you breathe in your heart rate increases, while breathing out decreases your heart rate. Your fight/flight/freeze response is triggered by an elevated heart rate, as if often experienced during strong emotions. However, a decrease in heart rate helps to engage your parasympathetic (relaxation) response system. To use breathing to calm your heart rate, be sure to use your diaphragm (place your hands just under where your ribs meet, and breathe so that your ‘belly’ expands under your hands). Then breathe so that you exhale for longer than you inhale. Keep this up for a few minutes so that your system has time to realise it is safe and engages the relaxation response system.

Notice your senses

Sit in a comfortable position focusing on each of your senses. Start with noticing physical sensations and properties of your body, and then expand your awareness to the space around you.

For example, slowly notice how your feet feel touching the ground. Push your feet downwards and feel the ground firmly beneath them. Now feel the seat of your chair beneath you, and straighten your back, being aware of it supporting you. Notice your breath - how it makes your body move and how it feels as you inhale and exhale. Can you hear your breathing?

Next, shift your attention to your arms and hands. Notice the feel of your clothes against your skin, and any jewellery, watches etc. Now, push your hands together and feel your muscles tense – notice your shoulder blades, arms and hands. Release the tension and feel the muscles relax as you rest your arms. Repeat this, and then gently move and stretch your arms and hands in a way that is comfortable for you.

Now move your focus to the space/room around you, moving your head to look around. Notice 5 things that you can see. Then pay attention to any noises, starting with sounds that are close to you, and then shifting to those further away. Take time to listen carefully and bring your awareness to sounds you may not usually notice.

Stretch and relax your body and notice the room around you. Remind yourself that you are present in this moment, and that you are safe.

Take a few moments to notice any differences in how you feel after doing this exercise.

Go for a brief walk

While walking, notice your breathing (how it feels, sounds – perhaps practice a few calming breaths), the way your clothes feel as you move, how your feet move and feel as you step, the temperature of the air on your skin, the movement of your arms. Then broaden your focus to pay attention to the sights, smells and sounds around you. You can even do this when walking short distances, such as between rooms or buildings.

Focused eating

Eat or chew something slowly. Focus on the details of what is going on inside your mouth and as you (eventually) swallow – taste, texture, movement, sounds etc. Notice any smells.

Focus on an object

Choose a nearby object. Focus on it, paying careful attention to its physical properties, such as shape, size, colour, texture, etc.

Consider checking in with your anxiety before and after a grounding activity, perhaps even rating it out of 10 both before and after, so that you notice any changes.

Remember that it is important to practice grounding, and other body-based skills, regularly when you are calm. As you get better at the skill, and strengthen your body’s calming relaxation response, you will be able to start using it effectively in progressively more intense emotional situations.

Shoulds and Musts

Do you ever find yourself saying or thinking ”I should” (or shouldn’t) or “I must”?. We might say this to ourselves when there is something that we feel we need to do or want to do.

This pattern of thinking which we call shoulds and musts is an unhelpful thinking style that every person may engage in from time to time. Unhelpful thinking styles can also become automatic habits that individuals may not realise they are engaging in. This becomes problematic when these thoughts cause an increase in anxiety and decrease in mood. When this happens regularly and consistently this may have a detrimental impact on an individual’s social, academic, occupational and personal life. It is common in anxiety disorders and depressive disorders that an individual’s symptoms may be maintained by unhelpful thinking styles such as shoulds and musts.

Saying or thinking I should, or I must often puts pressure on ourselves as it may set up unrealistic expectations. This may then cause us stress which may lead to procrastination and disappointment.

If you are somebody who may notice yourself having shoulds and musts thoughts, there are ways in which we can begin to filter our thoughts. This can help us determine whether the thought is realistic and fair which may alleviate some distress that the thought caused. It can be helpful to write the thought down, then ask yourself:

Am I putting more pressure on myself, setting up expectations of myself that are almost impossible? What would be more realistic?

When we are stressed or tired, we may be more prone to engaging in unhelpful thinking styles such as shoulds and musts. This can be managed by maintaining self-care strategies particularly during times of stress which may include, exercise, relaxation activities, stress relieving techniques and mindfulness.

When we begin to pay more attention to this pattern of thinking we can get better at stopping it in its tracks!

I’m a psychologist and I used Tiktok…

I recently used (viewed? downloaded? watched? whatever the correct verb is here!) TikTok and a few other similar video-platforms, including Reels on Instagram and Shorts on Youtube. My motivation here was a mix of curiosity (everyone seems to be using it) ease of access (I’ve had a few friends send a link to a variety of funny Tiktoks), and maybe a sense that I was getting old and needing to keep up ;)

Here are some reflections from my experiences:

It’s, on the whole, VERY entertaining.

- As I often am when on the internet, I was constantly amazed at people’s creativity and humour. Many creators are young people with an outstanding ability to film and edit videos from their home in a way that is very skilled, hilarious, personal, and attention-grabbing. Much of the content I saw was either funny or interesting or light-hearted. Content creators had built amazing communities around them and people appeared to feel genuinely connected to their internet friends. In times where the world and the news feels heavy and anxiety inducing, Tiktok felt engaging in an accessible and stress-free way.

It’s feels addictive.

- It became very easy use it in moments of boredom or stress – such as on my commute home on the train, or when avoiding a certain task at home or work, or when I was struggling to fall asleep. I felt my mind totally switch off and relax when watching Tiktok, in a way that became very reinforcing for my procrastination tendencies! Core processes in addiction are tolerance and withdrawal – I especially noticed my tolerance (in terms of how long I chose to spend on the app) increase!

It’s very easy to pass (huge) amounts of time.

- Despite the videos being very short (less than a minute), I was shocked at how much time can be spent on the app. A core reason for this, I think, is the ‘never ending’ aspect of the scrolling. On Youtube or Netflix a video ends, and on Facebook or Instagram your feed eventually becomes things you’ve seen before, however on Tiktok there appears to be a constant stream of new content with no end or natural ‘exit’ point. This means that in stopping using the app requires a lot of internal motivation, as there’s nothing extrinsic encouraging you to wrap up. However, as mentioned above, the app can be very engaging and addictive in a way that I noticed really reduced my self-regulation capacity.

You have very little control over content.

- Tiktok appears to rely very heavily on ‘The Alogrithm’ so you get shown the content it thinks you’ll engage with. Whilst the content I saw was (as above) mainly very funny or interesting, there were moments I was exposed to some concern videos – usually extremely sexual or sexualised, or unhelpful in relation to body image and eating (with a lot of content centred on dieting, exercise, food routines/rules, dieting, and body). I also saw a lot of content relating to mental health, with a huge variety of accuracy – spanning from extremely helpful content created by Psychologists themselves attempting to spread knowledge about psychological techniques and normalising particular symptoms, all the way to extremely unscientific or incorrect ‘facts’ about mental health (particularly regarding diagnoses).

It appeared to shift my attention span.

- Over the course of using the apps, I noticed myself more quickly bored by other, long(er) forms of entertainment. And not just movies or television episodes, but even longer form youtube videos. Reading books, journal publications, and newspaper articles also became trickier the longer they became. I had become used to the very short span of Tiktok videos in a way that very quickly engaged my brain. Watching some longer movies, I found myself thinking “why is it taking so long to get to ‘the point’?”. This was perhaps the most concerning aspect for me – a strong attention span is integral to me leading a fulfilling and functional life.

I haven’t really continued to use Tiktok following this mini-experiment, but I wouldn’t say I’ll be completing avoiding it either. This isn’t meant to be an endorsement of the app, or a fear-mongering warning either. I’ve reflected on my experiences I’ve mentioned in this blog and worked out how best to fit this form of entertainment and others like it in my life.

Judgments

Do you ever find yourself making evaluations about situations, other people, yourself or the world? This might look like believing something to be true about a particular situation rather than interpreting that situation based on what we actually see or have evidence for.

This pattern of thinking which we call judgments is an unhelpful thinking style that every person may engage in from time to time. Unhelpful thinking styles can also become automatic habits that individuals may not realise they are engaging in. This becomes problematic when these thoughts cause an increase in anxiety and decrease in mood. When this happens regularly and consistently this may have a detrimental impact on an individual’s social, academic, occupational and personal life. It is common in anxiety disorders and depressive disorders that an individual’s symptoms may be maintained by unhelpful thinking styles such as judgements.

We are constantly exposed to new situations and people and making judgements about things may help us to quickly evaluate something new. This can be helpful however it is important to be aware that if our judgements become separated from what may be true and/or negatively bias we may need some help managing them.

If you are somebody who may notice yourself having thoughts involving judgements, there are ways in which we can begin to filter our thoughts. This can help us determine whether the thought is realistic and fair which may alleviate some distress that the thought caused. It can be helpful to write the thought down, then ask yourself:

I’m making an evaluation about the situation or person. It’s how I make sense of the world, but that doesn’t mean my judgements are always right or helpful. Is there another perspective?

When we are stressed or tired, we may be more prone to engaging in unhelpful thinking styles such as judgments. This can be managed by maintaining self-care strategies particularly during times of stress which may include, exercise, relaxation activities, stress relieving techniques and mindfulness.

When we begin to pay more attention to this pattern of thinking we can get better at stopping it in its tracks!

What’s the difference between a Psychiatrist and a Psychologist?

This is perhaps the most common question I get when I tell people what I do for a living. It’s also a question I get from clients at times.

Whilst both Psychologists and Psychiatrists are both mental health professionals, there are important differences between the two.

Psychologist

A Psychologist is someone who has completed studies and training in psychology, that is, the study of the human mind and behaviour.

They have first completed 4 years of university study. If a Psychologist has a specific term before this title (such as ‘Clinical’, ‘Forensic’, ‘Educational’, ‘Organisational’) then they have completed specialist training in a specific area of Psychology. This involves a 2 year Masters degree and then a 2 year program following graduation in which Psychologists work and are supervised as they gain further specialised experience.

Psychologists cannot prescribe medication. They have the capacity to assess and diagnose mental health presentations, and they offer ‘talk’ or behavioural therapy as treatment. You do not need a GP referral to see a Psychologist – you can book and pay privately (that is, not receiving a Medicare rebate), however many people choose to seek a GP referral to see a rebate.

What are the different types of Psychologists?

- General Psychologist – have completed 4 years of undergraduate study (a Bachelors) and have not further specialised, although they may have gained many years of experience in an area of psychology

- Clinical Psychologist – have completed at least a 2 year postgraduate degree (Masters or PhD) to specialise in clinical psychology, which is the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of disorders

- Forensic Psychologist –have completed at least a 2 year postgraduate degree (Masters or PhD) to specialise in forensic psychology, which is

- Organisational Psychologist – have completed at least a 2 year postgraduate degree (Masters or PhD) to specialise in organisational psychology, which is concerned with matters of

Psychiatrist

A Psychiatrist is a specialist medical Doctor. They have completed university studies in medicine, then completed their intern and resident years in a hospital. They then complete specialist training in Psychiatry (whilst practising as a Doctor) in order to gain the extra title of ‘Psychiatrist’. This extra specialisation takes approximately 5 years, and involves rotations within various settings, examinations and assessments.

Psychiatrists, therefore, can prescribe medication. They have a holistic understanding of health and the human body. They can expertly assess and diagnose your symptoms, in the context of your health and functioning, and then prescribe medications (if necessary) to treat your diagnosis. Psychiatrists also have training in psychotherapy, and may do ‘talk therapy’ with clients as well as provide medication management.

Do I need to see a Psychiatrist?

Not everyone who experiences mental health concerns will want to or need to see a psychiatrist. Your GP will be able to discuss this with you, and refer you to a Psychiatrist if necessary. You will need a GP referral to see a Psychiatrist, in general. Your Psychologist may also suggest you see a Psychiatrist however, you will require a GP referral.

Whilst GPs can prescribe and manage a range of psychiatric medication, you may need to see see a psychiatrist if:

- You are prescribed a restricted form of medication (such as medication used to treat ADHD)

o Psychiatrists have the ability to prescribe specialist medications that are highly controlled and can’t be prescribed by GPs

- You have not responded to medication trialled so far

o Psychiatrists, given their expertise, may be able to help better manage your diagnosis with prescriptions for different medications that your GP is unfamiliar with. There are many ‘first line’ medications that may be trialled by you GP, but if these don’t seem to be assisting, then it may be time to see a Psychiatrist

- You would like a second (or third…) opinion

o Mental health is often very complex! Like in any profession, sometimes different people will have different opinions. It is important that clients know they are entitled to seek other opinions. Perhaps your GP or Psychologist has discussed a particular diagnosis with you, you may want to receive clarification from a Psychiatrist.

- You have multiple diagnoses and/or other health conditions

o Given their medical training, Psychiatrists are well placed to be able to manage complex psychiatric conditions, and/or people with comorbid health conditions.

(Note: This blog is specific to Australia. Whilst this explanation generally holds true internationally, registration and training requirements do vary.)

Expectations

I invite you to reflect on the idea that expectations underlie a portion of our daily unhappiness. Recall times when you have felt angry, guilty, hurt, frustrated, fearful, shameful or disappointed, and then consider whether such feelings may be connected to your expectations.

Expectations can affect us in many different forms. For example, we have expectations of ourselves, expectations of others in our lives, and perceived expectations from others. We all have a wealth of expectations that are linked to our needs, wants, values, and beliefs. They create a vision of how we think things ‘should’ be.

Expectations of ourselves are often the most demanding, and may include things like working harder, being a better parent/partner/daughter/son/colleague, being more successful, achieving weight/health goals, being more efficient, being happier, or always being the best at something/exceling. Expectations of others can also be onerous and frustrating. You may expect your partner to do more around the house, spend less money, share parenting better, instinctively understand how you feel or your point of view, or be less distracted. Or there may be times when you expect your child to be more responsible, more polite, less distracted, more committed to their school work, or less drawn to gaming.

Of course our expectations are not always unhelpful. They can be realistic and form the basis for ideas, inspiration, striving and exceling. But they become problematic when we are no longer present, and are instead focused on how things (and others) “should” be, act and feel. When we tell ourselves that we “should” be doing something, we are highlighting that we are not doing it. When others do not measure up to our expectations, it creates friction and frustration.

If we can notice and identify the expectations we have for ourselves and for others, we can question whether these expectations are realistic and helpful for us, or whether they are interfering with our living in line with our values and functioning well. By becoming conscious of when we are holding ourselves or someone else to an unrealistic standard, then we can keep the expectations that are comfortable and congruent with ourselves, and adjust the expectations that are not serving us well.

Take a moment to reflect on some of your expectations, or ‘shoulds’. Are they realistic? Are they really important? Are they congruent with how you want to be for yourself and others? Have they been communicated openly with the other people/person? If you openly clarify your expectations of others, and theirs of you, this can help determine whether expectations are reasonable and acceptable, while improving relationships with others.

Communicating about expectations, and identifying and changing unrealistic expectations, can lead to an ability to appreciate what is good in our lives, and be able to be compassionate both towards ourselves, and towards others. Consequently, when we give our best, we can feel like our best is good enough, and we can focus on being present and behaving like the person we want to be. This can also be achieved by practicing acceptance. By simply observing your expectations and not (re)acting on them. How might it feel to let go of the ‘shoulds’ and judgements? How might this affect your relationship with others? Might you feel more present, like you are ‘good enough’ and less like your goals are always out of reach?

Consider whether you are letting uncommunicated and unreasonable expectations of yourself and others get in the way of behaving like the person you want to be, your relationships with others, acting effectively and living the life you want.

If so (and I doubt many of us could say we aren’t!), by identifying expectations that can help us to align with our purpose and values, we can adjust our expectations and actions to be more helpful, compassionate and congruent with ourselves. To do this, take some time to identify adjusted realistic expectations in domains of your life such as relationships, work/education, personal growth, health and leisure, guided by the following:

· Are they based on how you want to behave, live and show up in the world - how you want to treat yourself, others and the world around you?

· Are they focused on the present (not the future)?

· Are they within your control?

· Are they important? Do they really matter?

· Can they serve as a guide to daily living?

Why are you so triggered by your child's emotions?

As I embark upon the final stages of pregnancy, I have been exploring how it feels like another opportunity to reflect upon myself as a parent. What mistakes have I made on the journey so far? What have I learned? What do I want to do differently this time around? What feels important to me in the way I raise and respond to my kids? And what is so difficult about being the kind of parent I want to be? These are big questions that many parents sometimes ponder, and the answers aren’t always easy!

Regardless of whether you have one or more children or are on the cusp of becoming a parent for the first time, parenting is an enormous gift for those of us that choose it. But it’s also extremely hard work. Children change us. They change our lives. it is an immense privilege to have so much power over a human life. And at the same time, it is one of the most challenging things many of us will ever experience. With the power to shape another life comes enormous responsibility….and exhaustion, self-sacrifice, and the unrelenting nature of having to continuously meet the needs of another human being as well as our own. Most parents care deeply about their children’s welfare, and when we care about something, we tend to put pressure on ourselves to do it well. And yet raising children is not as simple as knowing if we work hard, we will get the outcome we want! Children don’t always respond the way we want or expect them to. They are complex and ever-evolving. And sometimes no matter how hard we try, we struggle to feel like we are truly succeeding at parenting the way we want to.

Part of this is simply that we are all human, imperfect, and unable to meet the idealised and often unrealistic expectations we may hold for ourselves or for our child; but perhaps part of it is that being a parent triggers old wounds. Unconscious remnants of how we ourselves were parented. Thoughts, beliefs, internalised messages, emotions, and memories from a time we may not even consciously recall. And these things drive our actions far more than we may care to acknowledge. Despite our best intentions, we hear ourselves saying things we later regret. We don’t always hold the boundaries we plan to. We inadvertently lose our tempers, criticise, or shame our children. And sometimes we hurt them the way we ourselves were hurt. And in these moments, it’s often easier to blame them or see them as the problem. But if we really reflect, it’s not really about them and their behaviour at all. It’s about us, and the work we haven’t yet done to process and explore our own early experiences and the impact of these upon us.

This is not about bashing our own parents. After all, they were likely also doing the best they could with the knowledge, skills, and resources they had at the time. And these things were influenced by how they themselves were parented. The uncomfortable truth is simply that becoming a parent is like holding up a mirror to see parts of yourself that are difficult to acknowledge, or perhaps even parts of yourself that you didn’t even know existed!

Inside of all of us is that part that is vulnerable, that part that feels painful emotions like hurt, anxiety, loneliness, shame, and fear. And often the way our parents responded to us as a child influences how we ourselves respond when that vulnerable part of our child is right in front of us. Particularly if some of those emotions are so difficult for the child to experience or understand that they shift into anger instead. What a parent often sees as defiance, refusal to cooperate, being disrespectful, or “naughty” is actually their child’s signal they are stressed, overwhelmed, or unable to cope. But do we (and did our parents!) always recognise this? Similarly, when we react with anger, are we always in-tune and aware of our own more vulnerable emotions that often lurk underneath?

For most of us, it is distressing to see our child distressed. And despite our best intentions, the more they escalate, the more we do too. We’re often so desperate for them to calm down, or stop crying, or yelling, or to just co-operate and do what we want them to do, that we panic! Without even realising it, we’re no longer in control. Instead, we’re reacting from our own emotions. And these emotions are often driven by the unconscious internalised messages we picked up a long time ago.

So, if you find yourself struggling to hold the boundaries you try to set, or if you hear yourself snapping at your child when they say or do something that triggers you, or if you find yourself becoming frustrated with them not doing what you expect of them, it may help to ask: Why? Why does this bother me so much? Why does this hurt? Why does this feel so threatening or overwhelming to me? Why is this so hard for me to navigate?

And as you’re asking these questions, it’s important to let go of defensiveness and instead non-judgementally reflect on the deeper-seated emotions or experiences that are about more than just how your child is behaving in that moment.

Because sometimes, children have as much to teach us as we do them. And sometimes, doing this inner self-reflection allows us to see that in order to change the patterns of our child’s behaviour, we first need to recognise and change our own.

Critical Self

Do you ever find your internal voice being rather self-critical? This might look like blaming ourselves for something that isn’t completely our responsibility or being overly critical of our abilities in different areas of life. We might find ourselves saying “I can’t do anything right”, or “I’m not good enough”.

This pattern of thinking which we call self-criticism is an unhelpful thinking style that every person may engage in from time to time. Unhelpful thinking styles can also become automatic habits that individuals may not realise they are engaging in. This becomes problematic when these thoughts cause an increase in anxiety and decrease in mood. When this happens regularly and consistently this may have a detrimental impact on an individual’s social, academic, occupational and personal life. It is common in anxiety disorders and depressive disorders that an individual’s symptoms may be maintained by unhelpful thinking styles such as critical self.

Being aware of and evaluating our strengths and weaknesses can have many benefits for self-development. When we take a self-critical viewpoint, however, we may have trouble thinking about what strengths we have and find ourselves focusing on weaknesses that may or may not be there. This becomes problematic when it negatively impacts our self-esteem and self-confidence.

If you are somebody who may notice yourself having self-critical thoughts, there are ways in which we can begin to filter our thoughts. This can help us determine whether the thought is realistic and fair which may alleviate some distress that the thought caused. It can be helpful to write the thought down, then ask yourself:

The internal bully’s at it again, would someone who really knows me say this about me? It can be helpful to consider what we might say to a friend in a similar position.

When we are stressed or tired, we may be more prone to engaging in unhelpful thinking styles such as self-criticism. This can be managed by maintaining self-care strategies particularly during times of stress which may include, exercise, relaxation activities, stress relieving techniques and mindfulness.

When we begin to pay more attention to this pattern of thinking we can get better at stopping it in its tracks!

Do you know the stories you tell yourself?

Everyone has ‘off’ days. Everyone has moments or periods where they feel flat, sad, on edge, yuck/gross, disconnected, hopeless, guilty, or anxious. Often it’s not the mere presence of these feelings or experiences that contribute to mental health disorders, it’s the stories that our brain creates around these feelings.

Before we can work out if this story is true or false, helpful or unhelpful, workable or unworkable, we need to identify what the story is. Many different types of therapy (e.g. cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)) rely on us firstly recognising these stories!

Sometimes these stories are so sneaky and pervasive that we don’t even realise our brain is telling them to us. It can be helpful to take a step back at times and ask ourselves ‘what is my brain telling me in this moment?’. Recognising the types and patterns to the stories we create can help us catch our brain in the act next time that it’s doing it.

Here’s a (non-exhaustive) list of ones I’ve commonly seen in the therapy room:

1. The “I must figure out why I am feeling this way” story

Often we can get to the bottom of why we are feeling a certain way. However, sometimes (even with lots of therapy and introspection!) we just can’t. A common story I often see is people working themselves into a fluster trying and trying and trying to come to a definite conclusion about why they are feeling something. If their brain doesn’t get a ‘good enough’ answer then this story becomes stronger and stronger!

2. The “I’m bad/silly/wrong for feeling this way” story

This story often happens if we don’t feel like we have a good enough reason (see above!) to feel the way we’re feeling. This story often comes about if we’ve been shamed for feeling something or shamed for expressing certain emotions in the past. This story may be more common for those of us who like to be independent, or who struggle with perfectionism, or who may experience lots of negative self-talk.

3. The “I shouldn’t feel this way” story

This story goes hand in hand with the one above. We may notice a feeling, but we chastise ourselves for experiencing it. We minimise the feeling or the circumstances surrounding it, and try to avoid noticing the feeling or expressing it. This story says that the emotion we’re noticing is useless, embarrassing, unjustified, or simply lasting too long. Maybe we tell ourselves that “someone else wouldn’t be feeling this”. This story has a knack for then making us start to experience guilt or frustration on top of the original feeling!

4. The “If only xyz had happened, then I wouldn’t feel this way” story

Otherwise known as the ‘should coulda woulda’ story. This story loves to go through the past with a fine tooth comb – trying to work out what could’ve been different, what we (or someone else) should’ve done to avoid this feeling. Often we project forward with this story too; thinking of all the things we will/won’t do to never feel this way again. Sometimes we may even project this story onto others, we try and problem solve their issues or offer advice about what we would’ve done when differently when they tell us what they’re feeling.

5. The “I can’t cope with this feeling” story

Also known as the “This feeling is too big” story. This story makes us think that feeling is in control of us, rather than the other way around. This story tells us that the feeling is so big and out of control that we are incapable of managing it, incapable of working with it, incapable of continuing on whilst it’s still around, incapable of doing anything that will change it. This story can also play out in ‘if then’ scenarios, such as ifxyz happens then “I won’t cope”. This story’s loves creating avoidance – because we start to see avoidance as the best (or only!) way to cope.

6. The “I don’t want to feel this way” story

This story can be sneaky – sometimes so sneaky that it presents as a “I don’t know what I’m feeling” story. Not knowing what I’m feeling – aka emotional numbing – is a great way to just not feel something. We may also just consciously try and suppress, ignore, or shift a feeling, or deny that it’s there. We may pretend to ourselves or those around us that we’re not feeling a certain way. Sometimes this story may create unhelpful actions that allow us to escape (such as through use of substances or other addictive/compulsive behaviours).

7. The “This feeling will never go away” story

Similar to #5, this story creates the illusion that a feeling is here to stay and not going anywhere. It may join forces with the “There’s nothing I can do to shift this feeling” story and the “That won’t work” story to create a sense of apathy, hopelessness, and frustration. This story can be so hard when it shows up, because it can take away our ability to think clearly, see the light at the end of the tunnel, reach out to others for help, or think that change is possible.

As you read the above – are there any stories that you recognise here, or any others that you’d add?

Why FBT Could Be The Answer For Your Teen’s Eating Disorder

Family Based Treatment (FBT) is the most evidence-based approach for the treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and other restrictive eating disorders in adolescents. It is particularly suitable for those with a duration of illness of less than 3 years, which thankfully appears to be the case for a lot of teenagers. It is sometimes called the Maudsley Method due to originating at the Maudsley Hospital in London; and is a treatment which is often misunderstood.

When parents seek help for their teenager with an eating disorder, they are often feeling helpless, overwhelmed, frustrated, and utterly terrified! Often, they’ve been facing daily battles to get their child to eat. Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses, and Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of all. It often results in such a grip on the sufferer that it drives them away from their family and friends through rigid rules, social withdrawal, and challenging behaviours such as refusing to eat certain foods, exercising compulsively, bingeing, purging, or other secretive or deceptive behaviours. This means parents are often desperate for professionals to “cure” their child, and are often feeling powerless to know what to do themselves. It can therefore come as a surprise to many when the idea of a family-based approach is suggested. Many parents are quite reluctant at first, and I often hear things like “I really think they need individual treatment” and “We’ve tried to help and they won’t listen to us” and “We need you to get to the bottom of why they developed it in the first place”. All of these things make sense if you’re feeling like nothing you say or do is making a difference, or if you’re faced with a combative teen fighting your every move! However, if we think of Anorexia as being a serious illness that has hijacked their brain, the chance of them being able to independently make the changes required is often slim.

Research generally shows that when a teenager has a serious eating disorder, it’s not that they “won’t” eat normally, it’s that they “can’t”. They are so overwhelmed with the anxiety and distress the Anorexia creates, so terrified of getting fat, so fearful of foods, so caught up in the obsessionality or ridged rules, that they are literally paralysed. Their fight/flight/freeze response is kicked into action, their brain is starving, and their cognitive capacity to think logically and reasonably has shut down. This results in extreme distress, avoidance, or outbursts to the point where they literally cannot do it alone!

One underlying philosophy of FBT is that no one is to blame for the eating disorder developing, but families do need to step in and take responsibility for helping their loved one get well. We don’t ask families to be involved because we think they’re part of the problem, but because they are a critical part of the solution. They are the best resource in their child’s recovery due to the investment in love they have for their child! The simple truth is that in most cases, no one will fight harder to keep a child alive than their parents. It may sound dramatic, but this is a life-or-death situation. Anorexia kills. Whether it is due to the acute medical complications that can arise, a more chronic destruction of the body over time, or sometimes suicide, it is not something that can be brushed off. And even if the sufferer doesn’t actually die, their quality of life is often greatly reduced. Hopes and dreams, and even normal everyday functioning all fall by the wayside. And the longer it goes on, the harder it becomes to treat. It requires enormous courage and commitment to stop an eating disorder in its tracks. Enormous strength and resilience, and it often requires an entire family to come together to fight it.

Framed another way, if the child or teen were to attend weekly individual therapy sessions, that’s one hour per week that they have support, and 167 hours per week they are fighting a deadly illness alone. If the family all attends, that’s one hour a week the family has the support of the therapist, but 168 hours a week the young person has their family forming a team to support them through challenging meals and triggering situations in real-time. Which of these likely has the greatest power to get them well?

We don’t really know what causes one child to develop Anorexia and not another, but it is likely a combination of genetics, temperament, and life experiences. Another key part of FBT is that we cannot afford to spend time trying to figure that out when the child is facing serious medical and psychological consequences of the illness. Instead, we need to understand and break the patterns which are keeping it going and get them physically restored to health as soon as possible. There is a frequently used metaphor in FBT that focusing on the underlying cause of the illness, is like the child being in a sinking ship, and the parents swimming out and examining the boat’s engine to figure out what went wrong, whilst in the meanwhile their child is literally drowning!

The other reason it’s often critical to have the whole family involved is that eating disorders don’t just affect the individual, they affect the whole family system. Often the parents experience significant anxiety, stress, worry or anger due to the impacts of the Anorexia or the changes they observe in their child. Siblings feel helpless at their brother or sister becoming so unwell, or they miss out on the attention and connection they need because everyone is focused on the illness and all its manifestations. Often the whole family accommodates the illness by buying or cooking different foods to try to keep the peace, or they spend vast amounts of time trying to negotiate or cajole the sufferer to eat something. All the while the anorexia is gaining power over the whole family and the way they function. Often mealtimes are no longer fun times of connection but are a battleground which is stressful for all!

By having the whole family involved, everyone can share their experiences with each other, everyone can collaborate in helping their loved one get well, and everyone can feel confident they are playing a part in their loved one’s recovery rather than watching helplessly from the sidelines. Parents, siblings, families - your loved one needs you! You can be part of the solution for them! There is hope!

Just like any type of therapy, FBT won’t necessarily work for everyone. But if your child or teen is experiencing an eating disorder, it may be worth discussing with your treatment provider whether FBT could be the answer!

For more information the following resources may be helpful:

https://butterfly.org.au – The Butterfly Foundation

https://insideoutinstitute.org.au – The Inside Out Institute

HALTS - a brief check in tool

Everyone experiences fluctuations in their mood and functioning, regardless of whether they struggle with mental illness or not. Understanding what may be triggering these fluctuations can sometimes give us insight into how to adjust our thinking or behaviour in order to feel a bit better.

It has most often been used in substance use recovery as a guideline for people to identify the warning signs of a relapse. However, HALTS is a quick tool I often share with all clients, regardless of their presenting diagnosis, in order to build awareness about factors that may be contributing to a change in our mood.

HALTS is an acronym (which I’ll explain below), but also a reminder to ‘halt’ or take a pause when we’re feeling off – to spend a few moments being mindful of our internal world (asking ‘what’s going on for me right now?) and also our external world; our actions, routines and behaviours.

H – stands for hungry

There’s evidence to suggest to low blood sugar levels produces the same symptoms that anxiety does. That’s because when our blood sugar drops, our body produces a stress hormone (adrenaline). Colloquially, we may experience this as ‘hangry’. Feelings of hunger are usually our body’s signal that we need to eat*. Eating regularly (ideally three balanced meals spaced throughout the day) can assist us in managing our mood and anxiety symptoms. Making sure we’re well nourished before stressful events (such as exams, important meetings, or a job interview) can help not exacerbate natural stress responses and give our brain the critical fuel it needs to function properly.

*However, these signals may be more complicated if you have a history of disordered eating)

A – stands for angry

There’s nothing wrong with feeling angry (see my other blogs about the importance of not labelling feelings as ‘good’ or ‘bad’), but strong feelings of anger can similarly induce release of stress hormones triggering a ‘fight/flight/freeze’ response. Often when we’re in this mode, we’re possibly going to have a short fuse, feel frustrated by small inconveniences, find it hard to concentrate, be more agitated and maybe say or do things we don’t mean. Feelings of anger may be a sign that we’re feeling overwhelmed and need to take a break, or perhaps that something has disrupted our individual boundaries and we need to communicate this.

L – stands for lonely

Humans are wired for connection. Loneliness can sometimes be hard to notice, particularly if you’re quite busy. Sometimes we may even feel like we’ve had lots of time around other people, but we forget to check in whether we are feeling loved by and connected to those people. Feelings of loneliness are an internal sign to connect! Connection (to friends, family, even pets!) is an important way to manage and prevent mood deterioration.

T – stands for tired

Whilst low energy and fatigue are a symptom of mental ill-health, they can equally be a contributor. Tiredness can encapsulate both physical exhaustion, but also emotional or mental exhaustion. Tiredness is a signal to rest, relax and refresh. This may be just for a few minutes (such as taking a few deep breaths whilst you sit at your desk, or eating lunch outside), or few hours (such as planning a quiet Saturday, or going to a yoga class, or going to be a bit earlier), or a few days (such as booking some annual leave, or going on a holiday). I often remind clients that what relaxes us is very individual! Build your own list of ways that relax and refresh you and help reduce physical, emotional, or mental tiredness. Similarly, simply not doing anything is not always relaxing. Many of us can spend hours not doing anything, but we may not be recharging. We may simply be escaping, avoiding, or procrastinating – and thereby not fully reducing tiredness.

S – stands for stressed (or sick, or substances)

Stress can be acute or chronic. Most of us are very good at recognising acute stress – a typically shorter period of intense stress for example; a car accident, an exam period, a performance review, conflict with a loved one, a period of illness, a move in house. However, stress can also be chronic – often longer periods of less ‘intense’ but still impactful stress. Chronic stress can sometimes be hard to acknowledge, partly because the human body is so good at adapting! Like the frog in the boiling pot of water – we may not notice the way chronic stress builds up in the body. Chronic stress may look like relationship tension, financial insecurity, a global pandemic, or constant work pressure.

S can also stand for sick – are you feeling unwell? Is there a health condition that we may be not treating properly? Some self-compassion during or after periods of physical sickness can assist with good mental health.

S can also stand for substances. Substances of any and every type play often a significant role in our mental and emotional functioning. Consumption of ‘every day’ substances such as sugar and caffeine can contribute to mood fluctuations (even if it can be hard to acknowledge it!). Other legal substances, prescription or otherwise, are also associated with mood changes (such as alcohol, nicotine, benzodiazepines, or pain relief such as opioids). Illicit substances may also be impacting your mood, sometimes even days, weeks, or months after you’ve stopped using. Ceasing use of these may not be part of your treatment goals, but thinking about your substance use and how it may be impacting you can he helpful.

Emotional Reasoning

Do you ever find yourself engaging in emotional reasoning? This might look like having a strong emotional feeling in response to a thought and then consequently thinking the thought was true. For example, when waiting for feedback on a task at work, we might predict that the assessor will think poorly of the work which may cause us to experience difficult emotions. Emotional reasoning occurs when as a result of experiencing these difficult emotions we then believe our work was poor or that we aren’t good at our job despite not yet receiving feedback.

This pattern of thinking is called emotional reasoning, which is an unhelpful thinking style that every person tends to engage in from time to time. Unhelpful thinking styles can also become automatic habits that individuals may not realise they are engaging in. This becomes problematic when these thoughts cause an increase in anxiety and decrease in mood. When this happens regularly and consistently this may have a detrimental impact on an individual’s social, academic, occupational and personal life. It is common in anxiety disorders and depressive disorders that an individual’s symptoms may be maintained by unhelpful thinking styles such as emotional reasoning.

When we engage in emotional reasoning, because the emotions feel bad, we feel as though the situation must be bad. For example, because we feel anxious, we think that we must be in danger. When our emotions are strong, we often have increased trouble thinking rationally which may perpetuate the strong emotions causing a vicious cycle. Individuals often feel as though they have a clearer perspective on a situation once their emotional response has been effectively managed.

If you are somebody who may notice yourself engaging in emotional reasoning from time to time, there are ways in which we can begin to become more critical and analytical of our thoughts. This can help us determine whether the thought is realistic and fair which may alleviate some distress that the thought caused. It can be helpful to write the thought down, then ask yourself:

Just because it feels bad, doesn’t necessarily mean it is bad. My feelings are just a reaction to my thoughts – and thoughts are just automatic brain reflexes.

It is also important to be mindful of when we are stressed or tired as we may be more prone to engaging in unhelpful thinking styles such as emotional reasoning. This can be managed by maintaining self-care strategies particularly during times of stress which may include, exercise, healthy food, relaxation activities, stress relieving techniques and mindfulness.

When we begin to pay more attention to this pattern of thinking we can get better at stopping it in its tracks!

Black and White Thinking

Do you ever find yourself thinking all or nothing? This might look like making absolute statements about certain things such as thinking that something is either all good or all bad. For example, we might think things such as “I always get it wrong” or “I didn’t get accepted, I will always be a failure”.

This pattern of thinking is called black and white thinking, which is an unhelpful thinking style that every person tends to engage in from time to time. Unhelpful thinking styles can also become automatic habits that individuals may not realise they are engaging in. This becomes problematic when these thoughts cause an increase in anxiety and decrease in mood. When this happens regularly and consistently this may have a detrimental impact on an individual’s social, academic, occupational and personal life. It is common in anxiety disorders and depressive disorders that an individual’s symptoms may be maintained by unhelpful thinking styles such as black and white thinking.

We may engage in dichotomous thinking when we are trying to understand ourselves or a situation. When we find ourselves thinking from the perception of either end of the spectrum (for example, I’m either a success or a failure), we may struggle to see the reality of the situation. The reality may be somewhere in between the two ends of a spectrum within the ‘shades of grey’.

If you are somebody who may notice yourself engaging in black and white thinking from time to time, there are ways in which we can begin to become more critical and analytical of our thoughts. This can help us determine whether the thought is realistic and fair which may alleviate some distress that the thought caused. It can be helpful to write the thought down, then ask yourself:

Things aren’t either totally white or totally black – there are shades of grey. Where is this on the spectrum?

It is also important to be mindful of when we are stressed or tired as we may be more prone to engaging in unhelpful thinking styles such as black and white thinking. This can be managed by maintaining self-care strategies particularly during times of stress which may include, exercise, relaxation activities, stress relieving techniques and mindfulness.

When we begin to pay more attention to this pattern of thinking we can get better at stopping it in its tracks!

Exploring Self-Awareness: The Johari Window

The Johari Window is a tool that can help in improving self-awareness and better understanding relationships. Developed by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham (the term ‘Johari’ is derived from their names) in 1955, the Johari Window is a model that facilitates exploring the conscious and subconscious areas of your life, building self-awareness.

The Johari Window (pictured) encourages you to examine four different aspects of your relationship with the self, with the goal of increasing self-awareness. You are invited to consider aspects of yourself that you are open about, those parts of yourself that you keep to yourself, aspects that others are aware of while you are not, and the parts of yourself that you are not consciously aware of.

The Four Quadrants

The Johari Window has four quadrants, but the size of each will vary from person to person, depending on how open, private and self-aware they are. These four areas can be described in more detail as follows:

1. The Public or Open Self

This refers to the part of ourselves that we openly share with others, and that can be openly discussed, and jointly understood. This may include aspects of your personality, attitudes, behaviours, emotions, skills, and life views. Disclosing information about ourselves to others can build trust, and can lead to others sharing information about themselves.

2. The Private or Hidden Self

This is the part where information you know about yourself may be kept private or hidden knowingly. This may be because you do not have the ability to share, or because you are trying to protect yourself. Information in this part may include vulnerabilities, sensitive feelings, fears, and secrets, as well as characteristics you may be ashamed of. Of course, you could also choose to hide positive qualities through a sense of humility. You can choose whether to open up and share this information with others at any point.

3. The Blind Self

This refers to the parts of you that are recognised by others, but you are not aware of. This can be in positive and negative ways. For example, others may see your competence, but you may consider yourself to be ‘inadequate’ or ‘dumb’. Or, others may find you difficult to converse with, or a good listener, while you have been unable to recognise this.

You need to be courageous and be prepared to make yourself vulnerable to address this part, as it requires trusting others to give gentle and respectful, but honest, feedback. Consider asking trusted people to describe you in ways you may not be aware of, so that you can become aware of characteristics perceived by others. This will improve your self-awareness, and the quality of your relationships. However, it’s important to remember that, just because someone has described you in a particular way, does not make it true.

4. The Undiscovered Self

This is the part of yourself that both you and others are not aware of. These include not yet realised or tried abilities, hidden feelings, concealed traumas, conditioned behaviours from childhood, unrealised fears or aversions, and information buried in your subconscious.

How can it help?

The Johari Window can be used as a guide to different aspects of relating, and provide a path to increased self-awareness through openness, connectedness, and communication. In terms of the window diagram, this means increasing the size of the Public or Open Self, or decreasing the size of the ‘unknown’ quadrants.

You can expand your Public or Open Self part by disclosing more about your self (“Tell”), and hence reducing your Private or Hidden self. You could also work towards increasing your awareness of your Blind Self (“Ask”), or exploring your Undiscovered Self (“Explore”) part to make room for future growth.

Completing the Johari Window is a process of self-discovery that requires honest reflection to explore and understand your Private self, Blind Self and Undiscovered Self. By increasing your self-awareness, you can improve aspects of yourself such as your ability to identify and manage emotions, harness your strengths, increase flexibility and build self-confidence. The process may enable you to open areas for growth and free yourself from ingrained choices. Expanding your Public or Open Self can enable you to reclaim parts of yourself that you may have distanced yourself from to protect yourself. You can move closer to being open and authentic, and recognise some of your characteristics that may be causing suffering, resistance to being open and receptive, and be impacting your relationships with others.